10 Astounding Facts About Octopuses – the Ocean’s Clever Chameleons

Deep Sea Enigmas! 🐙

Deep Sea Enigmas! 🐙

Depending on who you talk to, octopuses are either soulful, sophisticated creatures or the stuff of deep-sea nightmares.

Indeed, they’re often fictionalized as slimy, eight-armed monsters that lurk in wait of prey. But get to know them a little better, and you’ll find that these cephalopods are, though strange and alienlike to behold, also totally fascinating creatures.

Here are 10 things you might not have known about octopuses (and yes, the plural is octopuses, not octopi!).

About two-thirds of an octopus’s neurons are actually located in its arms. This means the arms can taste, touch, and even act on their own accord, without input from the brain.

Some research has even found that after an arm is severed from the body it will continue to snatch up food and try to move it in the direction of where the creature’s mouth used to be.

Octopuses have not one, not two, but three hearts. Two of them pump blood to its gills, and a third heart keeps circulation flowing to the organs. This third heart stops every time the octopus is swimming, which may explain why they prefer to crawl (you’d get tired too, if one of your hearts stopped!)

BONUS FACT: As for the blood the hearts are pumping around? It’s blue, thanks to a pigment called hemocyanin.

Mating isn’t all that much better for males. Once they’ve done their part in the reproductive process, their lives accelerate towards their end.

Males can only live for a maximum of a few months after mating.

Blending in means a better chance of survival.

Luckily for octopuses, they can completely change their skin color and texture in under a second.

Contrast that to the famed chameleon, which can take several minutes to transform.

A female octopus can lay up to 400,000 eggs. From the moment they’re laid she spends her life protecting them, night and day —even giving up eating while she focuses on her egg-guarding duty. Typically, the eggs take at least five months to hatch, though one deep-sea octopus was observed to guard her eggs for almost 4.5 years! Job done, the female octopus will die shortly after her eggs are hatched.

It used to be thought that only vertebrates were smart enough to use objects as tools. Not so: some octopuses have been observed hoarding two halves of a coconut shell, which they carry around like a mobile home and assemble together when needed. Aquarium staff probably aren’t so surprised. Octopuses in captivity regularly solve puzzles, open jars, navigate obstacle courses, and even find cheeky ways to escape their tanks.

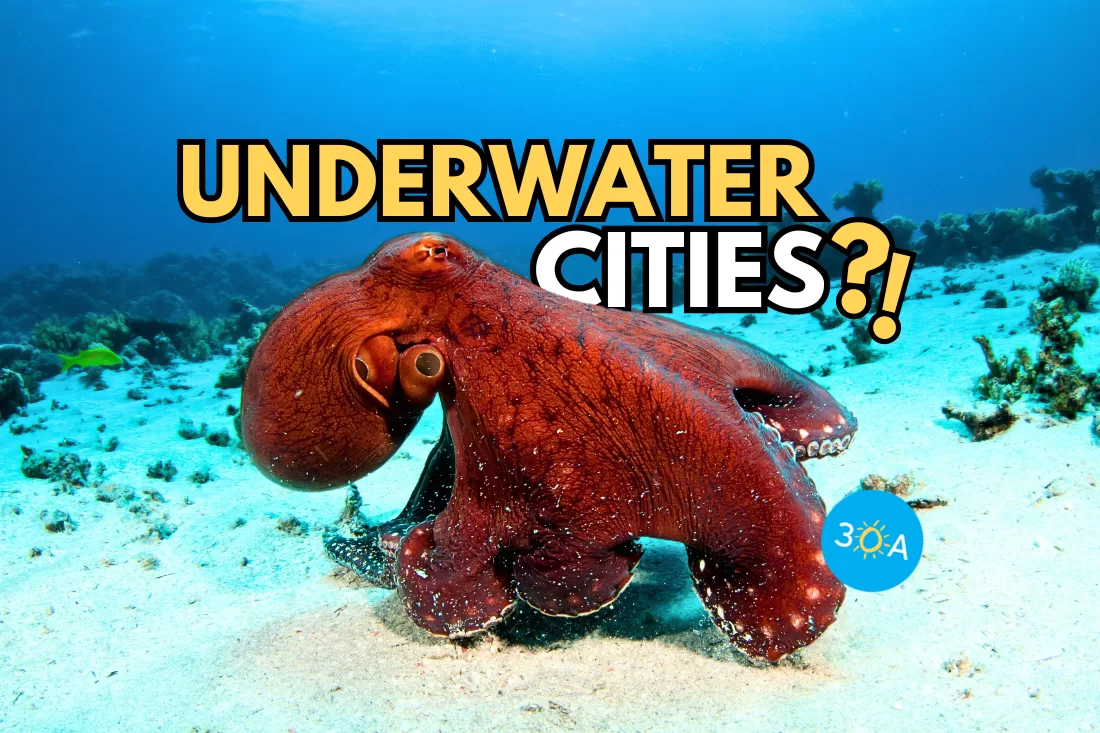

In 2017 scientists discovered an underwater octopus city, which they cleverly named “Octlantis”, off the coast of Eastern Australia.

It was populated by a species called the gloomy octopus which was previously thought to be solitary. The scientists witnesses complex social behaviors occurring in the population of 15 octopuses, who were living together, communicating, and even evicting each other from dens. It was the second such city found in the area after a first — “Octopolis” — was discovered in 2009.

Imagine you’re an octopus under attack. If your camouflage skills aren’t cutting it, you might want to detach one of your arms and let it crawl off on its own — the old decoy trick to distract the predator. Octopuses can actually do this and, as you know, grow the arm back later. They can also use their ink as a defense. Sprayed into the water, it reduces a predator’s vision and sense of smell.

If an octopus loses an arm — no problem! They have an impressive regenerative process that kicks in and allows them to develop a new one.

They’re also really good at it. When lizards regrow their tails, for example, the new one is often inferior. With octopuses, a regrown limb is basically as good as new.

Australia’s blue-ringed octopus is considered to be one of the world’s most venomous marine animals. Though only 5-8 inches in size, one octopus can carry enough venom to kill 26 adult humans and all within a matter of Their potent venom contains tetrodotoxin, which is 1,200 times more toxic than cyanide.